Blog | Reading Time 6 minutes

Brewing-Distilling inter-relationships (of the yeasty kind) by Prof. Graeme Walker

Brewing and distilling are sister industries

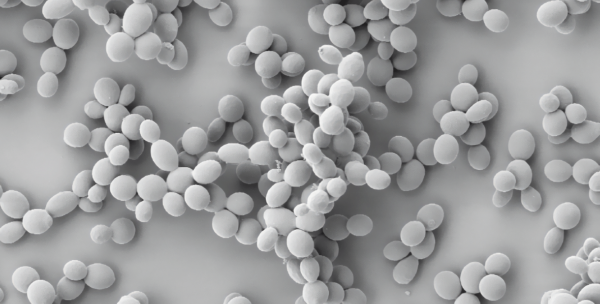

After all, as a Scottish distiller once told me: Beer is just whisky waiting to be made! There are many similarities, and of course some salient differences, between beer and spirits production processes. Nevertheless, the common denominator for all alcoholic beverages is yeast, most notably the species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This is the preeminent microbe responsible for bioconversion of starch and sugar substrates to ethanol, carbon dioxide and a myriad of secondary fermentation products that are collectively called f lavour congeners.

There are many brewing strains of S. cerevisiae — no one really knows the total number, but I would guess there are several thousand ale brewing yeast strains (although not nearly so many S. pastorianus lager strains, which are the new kids on the block). However, for distilled spirits there is by comparison a very limited number of commercially available distilling strains of S. cerevisiae (e.g. only a handful for Scotch whisky producers). It goes without saying that choice of yeast strain for beers and spirits is of paramount importance, not just for ensuring efficient alcoholic fermentation of the sugar or starch based substrate of choice but also to ensure the final organoleptic characteristics and consistency of the beverage. In addition, careful consideration of strain purity, yeast management, handling, propagation and pitching are critical for both brewers and distillers, together with microbiological control to prevent undesired contamination by bacteria and wild yeasts.

Although distillers strive primarily to achieve high ethanol yields in the wash prior to distillation, like brewers, they also need to produce a flavoursome wash that will result in a flavoursome distillate. The exceptions to this are when distillers aim to produce so-called “neutral” alcohol destined for spirits such as gin and vodka. This is also a pertinent consideration for brewers aiming to produce a neutral alcohol base for hard seltzers. Therefore, both brewers and distillers should pay careful attention when selecting yeast strains for specific fermentation applications whether they be for a f lavoursome or flavourless beer/wash.

The following comments aim to highlight selected areas, mainly relating to yeast and fermentation aspects, where brewers and distillers can learn from each other, with a particular focus on new developments in these respective sister industries.

What can brewers learn from distillers?

There have been some very interesting research and development initiatives over recent years that have benefited the distilled alcohol sector. The following represents a few selected examples that may potentially benefit future brewing practices.

- Neutral alcohol producing yeasts: As mentioned above, distillers producing neutral spirit destined for gin and vodka production, can select yeast strains that produce reduced levels of secondary fermentation metabolites (acids, alcohols, esters, etc.). Such strains (and fermentation practices) are pertinent for brewers wishing to enter the hard seltzer market sector.

- Very high ethanol fermentations: Some large-scale distillery facilities (eg. US corn ethanol plants) can routinely produce over 20% alcohol by volume following controlled fermentation practices (i.e. prior to distillation). Would this be of interest to brewers?

- Yeast strain engineering: The introduction of S. cerevisiae strains genetically engineered to produce starch-degrading enzymes such as glucoamylase have revolutionised corn-to-bioethanol production processes. These novel amylolytic yeasts could similarly lead to transformational changes in brewing and distilled spirits operations. Of course, some bioengineered yeasts have also been introduced to the brewing industry for sour beer fermentations, most notably Mascoma Sourvisiae™. Even newer developments in yeast gene editing and synthetic biology are on the horizon.

- Climate positive beverages: A Scottish craft distiller, Arbikie, has broken the mould in using the humble pea to produce the world’s first climate positive gin and vodka products. The use of legumes as adjuncts also for brewing has also found appeal since cultivation of such crops does not require application of environmentally-unfriendly fertilizers. For example, Barney’s brewery Cool Beans – faba bean IPA.

What can distillers learn from brewers?

- Fermentation Control: The operation and control of fermenters by brewers is something that distillers could certainly learn from. Whilst distillers rarely control, or at best have rudimentary control, of fermentation temperatures, brewery fermenters are typically quite tightly attemperated. This ensures a degree of control over yeast population dynamics (eg. flocculation) but also to govern the flavour characteristics of resultant beers. On a similar vein, the way in which some brewery propagators are operated could provide valuable insights to distillers, especially when endeavouring to maximise yield of viable yeast for pitching fermentations.

- Fermenter design: The vessel choices here for both brewers and distillers are wide: open v closed; steel v wooden; horizontal v vertical; cylindrical v rectangular; CIP v manual; etc. I contend that brewers have the upper hand here. For example, more estery beers emanate from the use of horizontal vessels.

- Microbiological control: Most brewers, but certainly not most distillers, operate hygienic practices to mitigate the effects of undesirable bacteria and wild yeasts. I’ll never forget when I was a student an elderly brewer told me there were 4 things to remember that will make a good beer: Quality Ingredients and Hygiene. I then asked what the other 2 things were, and he looked me in the eye and said: Hygiene and Hygiene. However, it is perhaps not advisable for distillers to follow some craft brewing practices involving spontaneous fermentations in coolships if striving for consistently high ethanol yields prior to distillation.

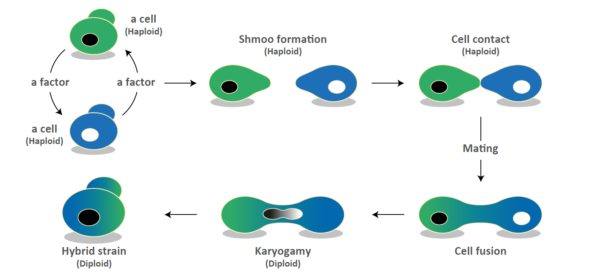

- Exploiting yeast biodiversity: Many craft brewers (and winemakers) are now using various strains of non-Saccharomyces yeasts for flavour diversification, either as mono- or co-cultures together with selected brewing strains of S. cerevisiae. These include strains of the following species: Brettanomyces, Lachancea, Torulaspora, and several others, that can elaborate beer flavour with phenolic, fruity, acidic and “funky” notes. Could such non-conventional yeasts be exploited for distilled spirit fermentations, including malt whisky? Watch this space…

Can brewers easily become distillers, and vice versa?

Many fantastic enterprising business examples are out there, but I would contend that the brewing-to-distilling pathway is not such an easy transition. Certainly not as easy as the reverse direction since distillers, to an extent, are already fairly accomplished brewers. For success in either enterprise, education and skills development are key. This is especially the case for technology transference from beer into spirit. Distilling requires specialist knowledge, not just from the process engineering perspective, but also from the health and safety and regulatory standpoints. For brewers with aspirations to diversify into distilling, Ethanol Technology Institute’s Alcohol Schools and the Siebel Institute’s Craft Distilling course are highly recommended.

by Prof. Graeme Walker, Professor of Zymology, Abertay University, Dundee, Scotland

Published Feb 9, 2023 | Updated Jul 23, 2023

Related articles

Need specific information?

Talk to an expert